Disabled Students in Nassau County Schools Feel the Brunt of Educational Inequality

BY: SARAH EMILY BAUM

(March 19, 2022) — Danielle Brooks was facing an uphill battle. In 2004, she was an African American mom to an 8-year-old boy with autism, John, who was struggling at his elementary school in Baldwin, New York. She knew she needed to fight to get him the accommodations he deserved.

But there were constant setbacks. Baldwin lacked inclusion classes, which would allow special education students like John to learn alongside their peers in general education classrooms. John’s classes were large and overwhelming for him. Administrators were also unfamiliar with John’s assistive learning technology, such as an AlphaSmart keyboard, needed to offset his difficulty writing — the result of his dysgraphia.

Then Brooks’ family moved from Baldwin, where students have some of the highest rates of economic disadvantage in Nassau County according the New York State Education Department, to the much more affluent Oceanside.

“There was an immediate difference,” Brooks told The Clocktower. She said Oceanside had more and better-trained staff. Oceanside had the inclusion classes which Baldwin lacked. Oceanside had smaller classes which were better for John’s learning needs. Most importantly for Brooks, Oceanside had a staff member in the district who specialized in assistive learning technology. Whereas Brooks said her son had struggled to access educational tech in Baldwin, she had options and ease obtaining that same accommodation in Oceanside.

“They had them here,” Brooks told The Clocktower. “There was no ordering them. There's no waiting for them. They didn’t have to hold a training on them. They already had them. They had a much higher level of special education services.”

Autistic activist Temple Grandon and a young John Brooks. SOURCE: Danielle Brooks.

See transcript of audio HERE.

Brooks observed what national literature has suggested for years — that a child’s zip code and familial income has drastic impacts on their educational prospects. She also noticed that race was another dividing factor. During the 2019-20 school year, almost half of all students in the Baldwin United Free School District were Black, compared to just 2% of the students at Oceanside.

“It’s not just about money,” Brooks said. “Less affluent districts are riddled by racism.”

While Brooks’ son was able to secure the academic accommodations he needed, not every family is so fortunate. A new analysis of Nassau County data by The Clocktower found widespread disparities among the treatment and outcomes of students with disabilities based on race and wealth. The findings follow national trends but are especially defined on Long Island, which has long since been considered one of the most segregated suburbs in America.

As a result, students with disabilities are suffering. And while non-disabled students feel the drastic impacts of redlining as well, The Clocktower found that, in some respects, the inequities are even starker for those with disabilities.

The Clocktower analysis used basic coding and web-scraping software to extract data from all 60 school districts across Nassau County. The Clocktower compared the percent of students in economically disadvantaged districts to multiple metrics of success. These factors included whether the districts met state targets, graduation and dropout rates, and the extent to which disabled students were granted access to the least restrictive educational environment as guaranteed by state and federal law. The analysis looked at K-12 districts, excluding charter schools and private schools.

The analysis included all disabled students, who, like their non-disabled peers, are diverse in their diagnoses, abilities and educational needs. Students’ disabilities ranged from learning disabilities such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and dyslexia, physical disabilities such as cerebral palsy and clinical blindness, and developmental disabilities such as autism and Down syndrome.

Not all students with disabilities may have the privilege of an accurate diagnosis or any diagnosis at all, which is especially true for women and youth of color. Some students with disabilities can go on to be educational high-achievers and pursue a college degree. Others may struggle to hold a full-time job and need 24/7 assistance for basic needs throughout adulthood.

All of these students are protected and supported by state and federal law. While one article cannot speak to the experiences of every one of the 26,643 students with a classified disability serviced by Nassau County schools in the last year, the data collected offers a snapshot of the hurdles disabled students face — one compounded by systemic inequities.

Oceanside Union Free School District did not reply to requests for comment. A spokesperson for Baldwin United Free School District declined to comment on particular cases but emphasized that the school follows all state and federal education guidelines.

The Clocktower’s analysis found that economic standing has a significant impact on student outcomes for both general education and special education students, but that it was most profound in the most economically disadvantaged communities. While the wealthiest districts graduated over 97% of their general education students and over 84% of their special education students, the poorest districts graduated only 87% in regular education classes and just 69% in special education.

The graduation disparity between the most and least affluent districts — 13% for general education students and almost 18% for special education students — indicates that a student’s disability will have a greater impact on their graduation potential if they attend schools in lower-income towns. Disabled students in the most economically challenged districts were also 50% more likely to drop out of high school than their non-disabled peers.

IMAGE: Long Island graduation rates for students in Special Education programs versus mainstream classrooms.

Being both economically disadvantaged and disabled becomes a double jeopardy for these students, according to Dr. Mawule Sevon, a school psychologist, behavior analyst and founder of Key Consulting Firm, which specializes in educational and mental health consulting for Black students.

“For children who live in those communities who also have a disability, then we're getting into this discussion around intersectionality,” she told The Clocktower. “You're marginalized from two different angles.”

In a region as redlined Long Island, where out of 219 communities most Black residents live in just 11, this divide becomes intrinsically racial. Educational disparities for low-income students of color with disabilities are similarly well-documented at the national level — impacted not only by material shortcomings but also by the attitudes of teachers and administrative bias, Sevon said.

“We're not giving them the same opportunities based on either race, ability, socioeconomic status, gender expression, or orientation,” she told The Clocktower. “All of these different factors change the way children are treated in schools. When I go into a school and I see over-restrictive environments for a particular group of students, it’s usually mirrored in an ideology that the adults hold that these students wouldn't be successful in a different type of environment. Do you believe that this child is capable of performing well in a mainstream classroom, or is your belief that you're just here to babysit them for several hours a day until they go home? What do you truly believe about this student, their capabilities, their community, their family?”

One of the most pronounced ways students with disabilities were treated differently in low-income districts, The Clocktower’s analysis found, was the extent to which disabled students in poorer areas were disciplined—a suspension rate almost 2.5 times higher in the most economically disadvantaged districts in Nassau County.

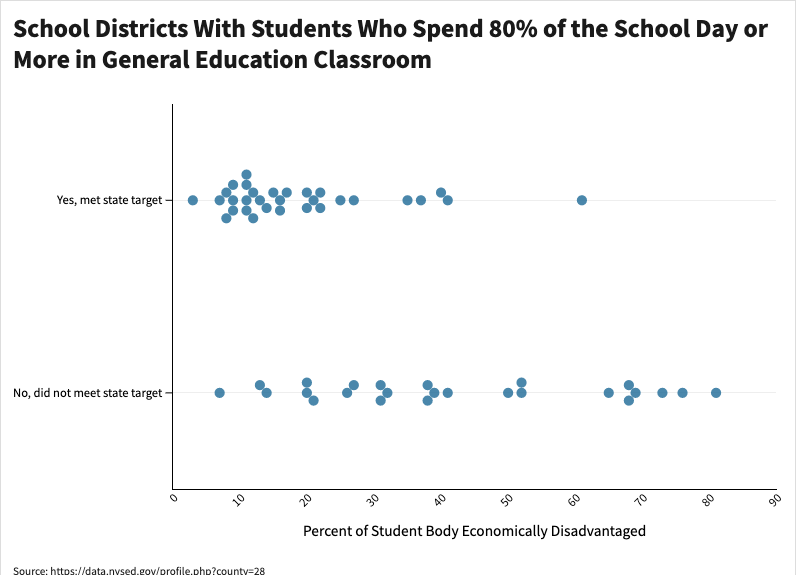

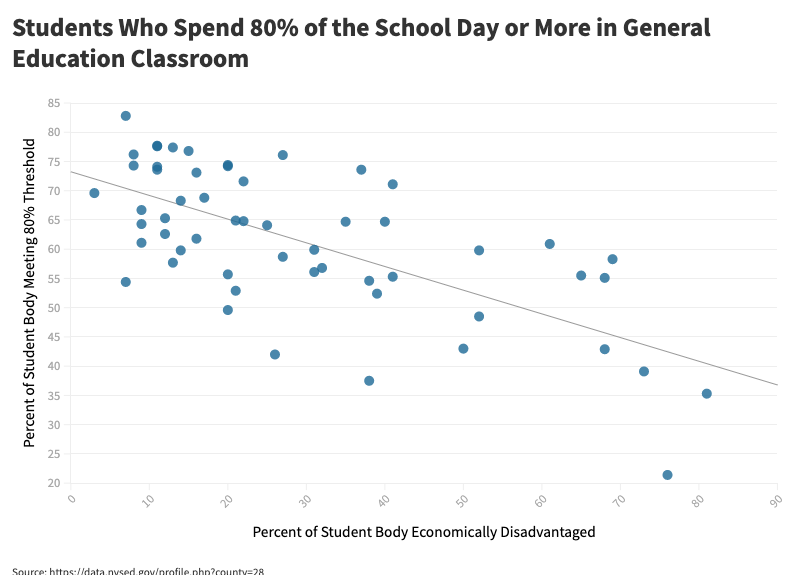

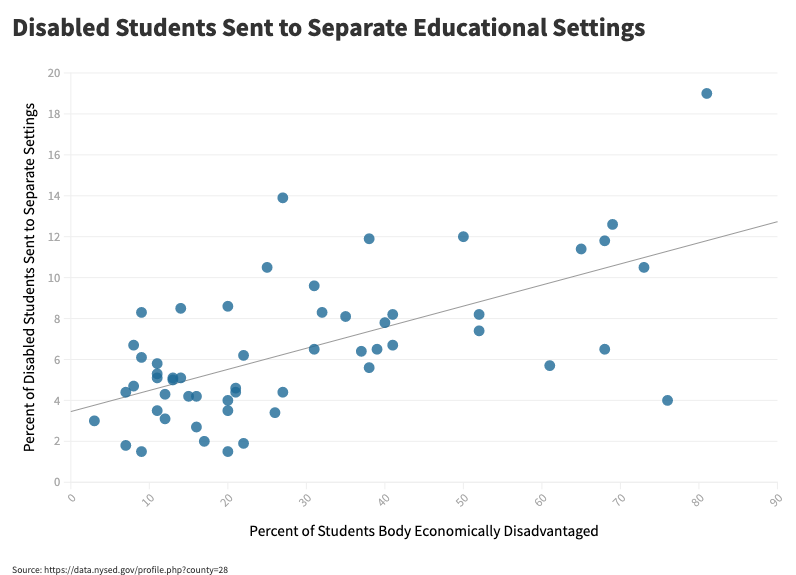

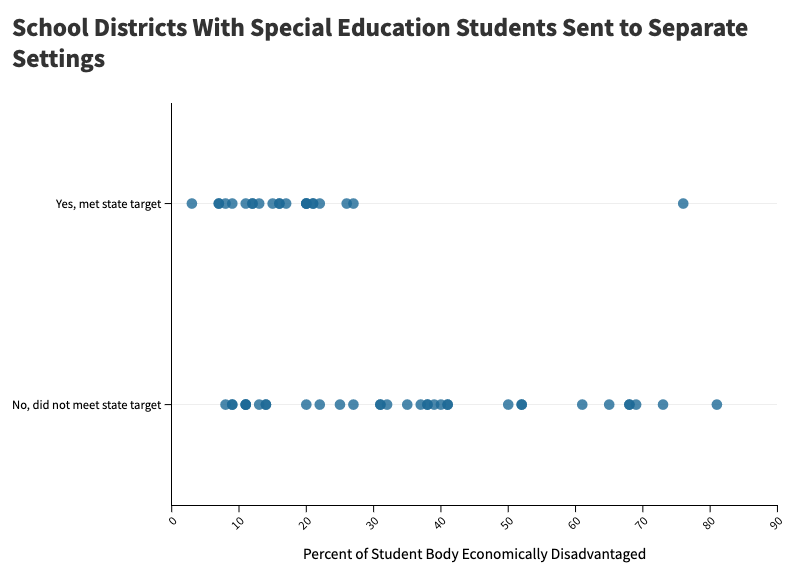

Moreover, widespread disparities exist when it comes to a district’s ability to meet state standards for classroom inclusion. The criteria dictates 60% or more of special education students should be in general education classes for 80% or more of the school day. (When not participating in general education classrooms, students may be placed in self-contained special education classrooms or out-of-district placements.) Only one out of the ten most economically challenged districts in the county met this benchmark, compared to 9 out of 10 of the most affluent ones. Students in the bottom economic quartile of schools were also significantly more likely to be sent out-of-district compared to more affluent schools.

Sevon said these measures are disproportionately employed against students of color. “They're in a more restrictive environment and they're not getting the same access to interventions,” she told The Clocktower. “We know that schools that are often in predominantly Black or Latinx communities engage in a lot more punitive practices, and have more of what I would call violent ways of addressing student behaviors. They're more likely to have police officers in their school, and whether students are neurotypical or have some type of educational disability or developmental disability, they're still exposed to the same type of harsh, ineffective disciplinary practices.” Sevon also noted disabled students of color are more likely to be impacted by the school-to-prison pipeline.

According to Dr. Matthew Krivoshey, Supervisor of Special Education at South Huntington UFSD and President of the Long Island Association of Special Education Administrators, keeping kids in the least restrictive environment is a labor-intensive process, but one that is “well worth it.” However, he said that schools in lower-income areas may not have the funding or initiative to train general education staff to work with behavioral or higher needs students who could otherwise be mainstreamed.

“I think districts get faced sometimes with a struggle: Do I have this kid in a general education class where he disrupts the education of 30 students, or do I put him in a class with maybe six or eight other students where the personnel and the numbers make it easier to manage him?” Krivoshey told The Clocktower. “It becomes easier to do that than it is to train staff and provide the resources to be able to include that student in a less restrictive environment.”

Much of the protections that disabled Americans have today were influenced by the 1972 exposé of the Willowbrook State School in Staten Island. At its peak, the government-run institution had over 6,000 disabled residents who were routinely abused, neglected and brutalized. Lawmakers declared it would be a reckoning for disabled Americans and that all children, regardless of ability, deserved decency, humanity and a quality education.

The uproar would lead to the passage of a series of laws promoting the rights and education of disabled Americans, culminating in the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (1990) and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (1990). These policies provided guidelines for schools servicing disabled students. The latter codified the idea that “a free appropriate public education must be available to all children residing in the State between the ages of 3 and 21…including children with disabilities.”

According to Dr. George Giuliani, the former Director of the Special Education Program at Hofstra University who now works there as a professor, these policies also stipulate that budgetary concerns cannot be used by schools to justify a lack of services. “Insufficient funding can never be the basis for educational decision-making when it comes to students with disabilities,” he told The Clocktower. “Find the money. That’s what the law says. You find a way, but you’re not going to deny the child a right to a free and appropriate public education.”

Fifty years after the Willowbrook documentary, stronger protections do exist for disabled children. However, the educational landscape is still a far cry from the ambitious goals set out by the ADA and IDEA.

While IDEA guarantees 40% of funding per pupil for special education students will be provided by the federal government, the actual number hovers around 16%. The Department of Education did release an additional $3 billion to special needs public school services nationwide, however, for the 2021 fiscal year, schools would still need $20 billion more to meet the IDEA’s benchmark.

As a result, spending may differ depending on where disabled students attend school. Once again, the contrast was especially drastic for disabled students. The Clocktower found that while the most affluent schools spent 13% more per general education pupil compared to lower-income districts, that differential jumped to 23% more per pupil when it came to special education.

Therefore, despite legal guarantees, the reality is much bleaker according to Krivoshey. “Very often, the special education budget for a district could be as much as a quarter of the budget for the entire district,” he said. “There is a monetary factor because the federal government, when they had created the IDEA, did so with the idea that the federal government was going to fund this so that the impact on the local taxpayer and the impact on the local school district would be mitigated.”

But that didn’t happen. In states like New York, where over half of school funding comes from local sources, the districts in poorer areas with less tax revenue are saddled with funding challenges.

“It's been my experience that there's a lot of dedicated people in this area that try to do the best they can with what they have,” Krivoshey said. “It’s their goal to provide the best services for kids they can, but money becomes an issue, politics becomes an issue. And I think sometimes it interferes with that mission.”

Danielle Brooks and her son, John, at a special education advocacy workshop. SOURCE: John Brooks.

Danielle Brooks knows about these conflicts well. After fighting for her son John to get the accommodations he needed, she founded Special Kids Advocacy Agency so that she could help other parents of disabled students advocate for their children. Brooks and her business partner, Maria Licata — both African American moms to young people with disabilities — work with parents of disabled youth across Long Island to fight to secure the accommodations that should be guaranteed by law.

Neither mother initially set out to make special education advocacy their full-time job. However, like many parents of students with disabilities, they found themselves “accidental advocates.”

“One day the speech pathologist called us and said, ‘If you don't fight for them, they're gonna lose their services.’ And that's where it began,” Brooks told The Clocktower. “Parents who are more involved have a better outcome. Districts that have more parents that are more involved have the best outcomes.”

For Brooks, this meant organizing a Special Education PTA in Baldwin, attending national conventions for advocates, attending town board meetings, and becoming an expert on state and federal law to know what her child was entitled to. She now attends meetings with other parents in need of an expert advocate, and she holds workshops where John also talks about his own experiences in self-advocacy.

At the same time, she admits it’s a time-intensive process, made easier by her college education and the privilege of a steady, dual-income household. Therefore, parents most impacted by class-based and race-based educational disparities may have to struggle the most to fight for their child, Brooks said. They may not be able to take off work to attend every PTA meeting or have a college degree to help them parse through bureaucratic jargon. They may be first-generation Americans and not even speak English.

“They need strong voices for the special needs community,” said Brooks. “But if I'm a single mother and I have a child with a disability, I have to worry more about putting food on the table than what that child is getting at school. They’re not to blame. It’s what the system does.”

Even in the most affluent districts on Long Island, disabled students face a myriad of bureaucratic and even legal hurdles. Conflicts with school boards and administrators routinely escalate to full-fledged lengthy and costly legal battles, according to Sevon, who has worked with many parents like Brooks.

“[Parents] don't have the opportunity or the time to get an attorney,” said Sevon. “Education is a global right. So why, in America, do you need an attorney to come to all your child's meetings to advocate for the thing they have a right to get?”